What Does One Vote Really Mean?

What gives a man the courage to reinvent himself over and over again, each time in a new language, a new country, a new occupation? How can a person find the fortitude to step into different cultures, to ask haltingly for work, to eat strange food and make new friends, to learn to read like a kindergarten child, again and again and again? And then to adopt that country’s values as his own?

My father-in-law, Paul Kraut, was such a man. He called himself a greenhorn, disparaging his immigrant status. “I’m just a greenhorn,” he would insist, “so I don’t know much, but…” and then he would say something really smart.

He came to the United States in his mid-thirties, stepping off the train from Mexico in a white suit with a white Panama hat. He looked, they said, like a movie star. People stared at this six foot tall, handsome man carrying a pearl handled cane, his blonde hair smoothed back in a pompadour, his blue eyes snapping. He must be somebody, that’s what they said. Only he knew that he wasn’t. He was a wandering Jew fleeing from danger, poverty and famine and following jobs and opportunities wherever they took him.

He came to New York from Chihuahua, Mexico, and before that from Vera Cruz, and before that Holland, and before that Germany, and before that Lithuania. He was fourteen years old when his family sent him from his small village to a town in Germany to apprentice as a mechanic at a distant relative’s home. . There he had to adopt new words, paragraphs, in hesitating convoluted sentences and learn German. At seventeen he was drafted into the German army of World War I, driving an ambulance over the brown barren Russian war fields. In the grinding post-war depression in Germany there was no work. He migrated to Holland with a friend and they talked themselves into jobs with a German steamship company, claiming they could work the steam engines, although they’d never done it before. They sailed to Central America learning the mechanics of steamships, cruising between the old and the new worlds and, after a few years, getting off in Vera Cruz, charmed by the weather, the beauty of the country and the prospect of helping to build a telephone system in Chihuahua, Mexico.

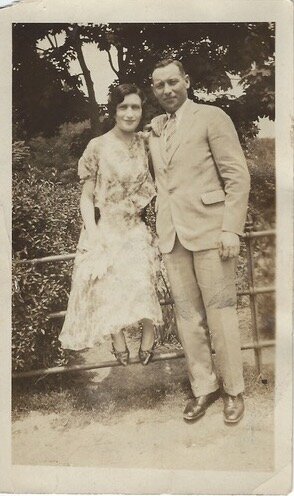

I think of him there, for the next ten years, riding a horse, working in an alien world, the cadences of his native Yiddish and his German, fading in his memory, mingling with his new language. I imagine him courting the dark haired Mexican girls with their flashing black eyes, in accented Spanish, and I see him as he was in a sepia photograph paddling a canoe with a beautiful young woman.

When he finally came to New York City to help his widowed sister, his Yiddish was almost forgotten he had not spoken it for so long. He had every intention of going back to Mexico where, he said, his life was good. But in New York he met a young woman who came from a village near his birth place, and they fell in love and married. He never returned to Mexico.

He remade his life again, learning to install and repair elevators in Manhattan buildings, starting his own small business, living in a small apartment in the Bronx and raising two sons, one of whom became my husband.

When I married his older son, Papa was still a handsome man. His blonde hair was almost white then, but still a full head. His blue eyes flashed with humor, and he spoke English, his fourth language, fluently, but with a heavy accent often liberally laced with Yiddish words. He loved me from the first, but he later told me that he was embarrassed before me and my American born family. He apologized for his accented English; for the black grease lines that were under his nails which, try as he might he could not completely erase when he scrubbed his hands; for the missing pointer finger on his right hand which had been cut off by an errant elevator cable; for his lack of formal education. I in turn loved and admired him, for all the adventure of his life, the start-ups and risk-taking which was so different from my family’s root-bound New York life. Here was an example of how one could strike out and live life with adventure.

But when I think of it now, I realize that wonderful as those traits were, they were not the essence of his character. Risk-taking and adventure was more a product of necessity than choice. It was the way he adapted and flourished wherever he lived, that was most admirable.

Here in America he gave up the adventure and lived simply. He drove his car, he lived in a small apartment in the Bronx, he took modest vacations in the Catskill Mountains of New York or Miami Florida, or on hot summer days simply went to Orchard Beach. He would say, “I have a dollar or two. I get by.” He was an independent man, always offering help, never asking for it. He believed strongly in gender roles. He was the breadwinner, his beloved wife the homemaker. But when she became too infirm to cook he did not hesitate to take over in the kitchen and vacuum the floors.

My father-in-law was one of the proudest Americans I knew. He adopted every American custom he could, from watching the baseball games his two sons played, to leading their Boy Scout troops, taking them for hiking and camping trips in upstate New York. He was a devoted husband and father, uncle and surrogate father to his sister’s children. He embraced his wife’s extended family, and helped to sponsor cousins who survived World War II into the United States so they could resurrect their lives. And when he had grandchildren he was an adoring and devoted grandfather to them.

His was the quintessential American immigrant story, not that different from many others, but I was intrigued by it. Growing up I had never thought much about how lucky I was to have been born in the United States. I took for granted my home, the food on the table, my free education, my car, my clothes, my comfort. I didn’t really think about my good fortune until one stormy November day. My mother-in-law was sick and Papa telephoned and asked me to come to stay with her while he went to vote.

“It’s so nasty out,” I said. “It’s not so terrible if you miss this time. It’s only a mid-year election.”

His voice shook with indignation. “I will vote. Every year I vote. I don’t miss because of rain. If you don’t come I’ll find another way.”

I came. He went out into the rain and returned with his dripping umbrella, sat down at the kitchen table and over coffee talked and talked about where he came from, what it was like being an outsider, not belonging, spilling pain and loss and memories. “Here, I belong,” he said. “I may be a greenhorn, but I have the same right as you.” His eyes blazed, and I was ashamed of myself. He reached across the table, took my hand and said, “You go home and vote.” I did.

He is gone now, but I remember him. I see him sitting at the beach beside his wife, cheese sandwiches and thermos of coffee on the blanket, staring out at the gray Atlantic Ocean remembering where he had come from. He may have felt that he was ever a greenhorn in this big American world, no matter how long he lived here, but to me he was an example of everything that is wonderful about this country. He brought his vitality, energy and hope with him and on it he built a strong and lasting legacy. And I never miss voting in an election.

Paul and Ida Kraut in the early years